US slave owners wrote and spoke about liberty, equality and the pursuit of happiness. Similar hypocrisy, buried in the foundations of settler Australia, has escaped comparable scrutiny.

The nature of the early settlements is so well known that it is frequently taken for granted. But for the first 50 years New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land were, above all else, places for the punishment by transportation, of property theft. Local courts also handed out severe punishment for theft. In many ways the sanctity of private property rivalled the sanctity of life itself.

This was all done in accordance with the common law as it operated at the time. This law struck a balance between the Commons (the British people) and the Crown.

The 17th-century jurist Sir Christopher Yelverton explained

…that no man’s property can legally be taken from him or invaded by the direct act or command of the sovereign [ie. the King], without the consent of the subject … is a jus indigene, an old home born truth, declared true by diverse statutes of the realmThe laws with which the colony was founded also declared that Aboriginal people became subjects of the Crown, which should have given them protection under British law. This created a problem of timing. Did the British seize the land of Aboriginal people before Aboriginal people became Crown subjects? Some law experts have suggested this may have been the case.

In the High Court in 1913 Justice Isaacs explained how he saw the situation:

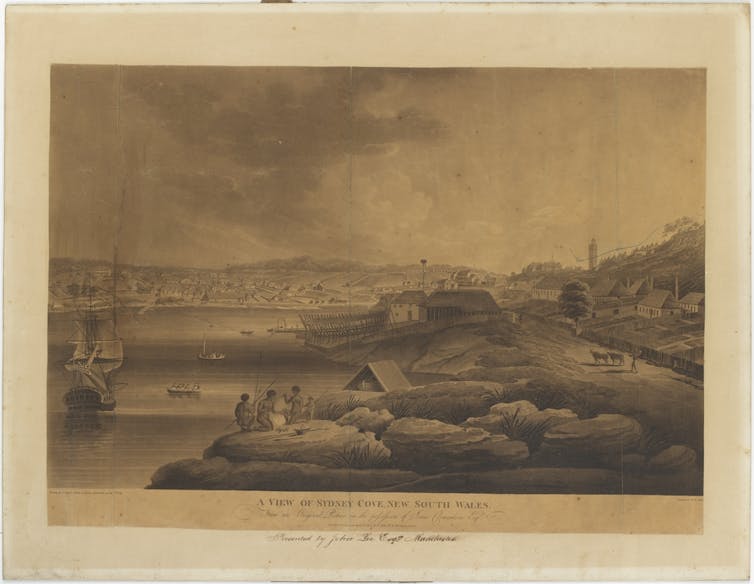

So we start with the unquestionable position that, when Governor Phillip received his first Commission from King George III on 12th October 1786 the whole of the lands of Australia were already in law the property of the King of England.It seems more likely that the the great legal moment came when the British actually arrived at Sydney Cove and formally read the legal instruments on February 7, 1788. But this still does not explain how Aboriginal people became subjects and lost their land at the same time.

Who gave us the terra nullius myth?

The only judicial explanation for what happened was provided in a judgement in the little-known Privy Council case of Cooper v Stewart in 1889. The case found that at the time of first settlement, New South Wales was “a tract of territory, practically uninhabited, without settled inhabitants”. This was regarded as binding on Australian courts until the 1970s.If that had indeed been the case then much of the continent would have been literally a terra nullius, a “nobody’s land”.

Why did the British think this? As it happens, this was the advice of Sir Joseph Banks, a man of power and influence – an aristocrat, President of the Royal Society and, even more importantly, a member of Cook’s expedition of 1770. In his writing and in evidence to Britain’s parliamentary committees, Banks declared that the long coast of eastern Australia was “thinly inhabited even to admiration”. As for the vast hinterland, of which he knew nothing, he said that it was almost certainly uninhabited.

It seems a perfectly reasonable assumption that this advice had a decisive influence on both the decision to send an expedition to Botany Bay, and to justify a lack of recognition of Aboriginal sovereignty or property. This was a fundamental departure from well-established precedents in the North American colonies.

Throughout the 18th century the American colonial governments negotiated treaties with Native Americans, and this practice was carried on by the American republic after independence from Britain. In Canada, treaty-making continued until the early 20th century and has resumed in recent years. The underlying assumption was that indigenous peoples were landowners and also held a form of sovereignty.

The British decision to depart from this path in the settlement of New South Wales had disastrous consequences for the Australians, and predetermined much of the violence that characterised the outward spread of settlement for more than a century. The British imperial government carries a heavy burden of responsibility for the horrors that unfolded.

It may have been the result of the mistake of making fundamental and portentous decisions before the First Fleet had even set sail. But ignorance does not lighten the burden of responsibility. Clearly no convicts were ever excused by claiming their theft had all been a mistake and that they thought the stolen property in question belonged to no one.

More troubling is that it took Australian courts until the 1992 Mabo decision to provide some limited remediation, but not reparation, for one of the greatest land grabs in modern history.

The incurable flaw

There were people at the time who were troubled by the way the annexation had taken place. When Governor King was preparing to hand power over to his chosen successor William Bligh he provided him with notes to help with his orientation including the observation about the Aborigines and that he had “ever considered them the real proprietors of the soil.”At much the same time in Britain the great political philosopher Jeremy Bentham wrote a pamphlet criticising the legal arrangements that had been made for the settlement of New South Wales. Among many points he made was the observation that there had been no negotiation with the Aborigines and no treaty had been signed with them. This created problems which would be enduring. “The flaw”, he declared, would be “an incurable one.”

Similar concerns about the conduct of the settlers, the fate of the Aboriginal people and the linked problems of property and sovereignty continued to be expressed across the generations by men and women who responded to the “whispering in their hearts” (a whispering first raised by Sydney barrister Richard Windeyer in 1842). They are part of the most enduring political debate in our history. They are still with us as Bentham predicted more than 200 years ago.

The problem is that there is no clear explanation in Australian legal theory to show how sovereignty passed from the first nations to the British crown. On this matter international law has been clear since the 18th century. Sovereignty can be lost and acquired either by conquest or by cession, that is, by the negotiation of a treaty. This was clearly understood by Bentham.

So what can be done? Ideally we should have a decision from the High Court. They could revisit the Mabo judgement and consider the question of sovereignty as Eddie Mabo himself wanted it settled. The case would be simpler than one which considered the actions of the British Imperial government. Murray Island was annexed by the Queensland colonial administration in 1879.

And if the High Court argues that it is unable to decide on such a question, the way forward may be an appeal to the International Court of Justice for an opinion on the matter. That would clear the way for treaty making in Australia itself which would finally provide a cure for Bentham’s flaw.

Henry Reynold’s The Whispering in Our Hearts Revisited has recently been published by NewSouth.

Henry Reynolds, Honorary Research Professor, Aboriginal Studies Global Cultures & Languages, University of Tasmania

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

No comments:

Post a Comment